February 2026

A belated happy new year. Please see the contents of our first newsletter of 2026 below.

NEWS

New paper: Understanding parents’ experiences of using a portion guide for young children: A qualitative study

Infant milk news

BFLG-UK news

New video: What are the solutions to the infant formula affordability crisis?

New policy paper: Joint Government response to the CMA formula market study

Forthcoming

News

Updated: Eating Well in Healthy Pregnancy: A practical guide to support teenagers

This practical guide is all about supporting pregnant teenagers aged up to 19 (and their families) to shift the balance towards better food choices wherever possible and show what eating well really looks like, with practical advice on how to do it. It shows the sorts of foods and amounts of foods that will meet the nutritional needs of young women in pregnancy and give the best start to the baby.

As with all our resources, this guide is evidence-based and has been produced independently of any industry support. There remains a paucity of truly independent advice on diets in pregnancy, and caution that commercially supported advice may provide recommendations that are inconsistent with public health recommendations.

The changes we have made in this 2026 update mostly reflect either the new NICE Maternal and Child Nutrition Guidelines (NG247) or the more challenging context in which pregnant women are trying to eat well since we last updated the resource in 2022.

Changes include:

Revised content on weight management and talking to young women about weight in line with NICE guidelines

Additional signposting for young women on low incomes, as recommended by NICE

Updated content on Healthy Start and Best Start schemes

Updated meal and snack price banding (as prices have gone up)

Updated content on sweeteners and plant-based milk alternatives in line with SACN recommendations

Updated recommendations on micronutrient supplementation in line with NICE guidelines

Added specific micronutrient requirements for teenagers who are pregnant.

Updated content addressing common barriers to eating well in pregnancy, especially related to poverty

A couple of additions to foods to avoid (products containing cannabidiol and raw enoki mushrooms)

Updated directory of additional resources

To download a FREE PDF copy of this guide, or any of our other 12 Eating Well guides, visit our shop. Donations are welcome. This guide and other selected Eating Well guides are also available for sale as hard copies in our shop.

Updated: Eating Well: Vegan infants and under-5s

This practical guide has been created to equip parents and carers who wish to raise their babies and young children as vegan, with the knowledge and practical advice to do so in a way that will meet their nutritional needs. It is also relevant for feeding under-5s on dairy and egg-free diets, and for early years settings needing to cater for these dietary requirements for babies and young children in their care. It shows the sorts and amounts of foods and necessary supplements to meet the nutritional needs of under-5s on these special diets.

The resource contains:

a summary of the key principles of eating well for vegan infants and 1-4 year olds

some example meals and finger foods to show how the nutritional needs of vegan infants can be met

example breakfasts, snacks, savoury meals and desserts for 1-4 year olds, with recipes for the dishes shown in the photos, and

additional useful information for anyone supporting vegan under-5s.

We noticed when we updated it that it remains fairly unique, as there remains little other detailed expert advice for these specific age groups. The changes we have made in this 2025 update reflects the latest advice from the Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition and the Committee on Toxicity on plant-based drinks and from the NHS on commercial baby foods. We have also made changes to ensure the most up to date information on the current retail offer for formula milks, plant-based drinks and supplements.

It is likely that parents who choose a vegan diet will be keen to breastfeed their children, and parents should be fully supported in this choice. There are no vegan infant formulas approved for sale in the UK. While soya formula was once recommended, this is judged unsuitable for use under 6 months of age and is no longer available. Plant-based formula milks can be purchased from overseas and at least one if now available in UK pharmacies, but these are either not in line with UK regulations or are intended for use under medical supervision by formula fed babies who are not able to drink standard infant formula due to allergy.

To download a FREE PDF copy of our guide ‘Eating Well: Vegan infants and under-5s’ or any of our other 12 Eating Well guides, visit our shop. Donations are welcome. This guide and other selected Eating Well guides are also available for sale as hard copies in our shop.

For more information on vegan diets in the early years, see our recent blog for the Maternity and Midwifery Forum: Veganuary 2026: Raising a vegan baby or toddler requires careful planning.

New: A Breastfeeding and Infant Feeding Vision for the UK

On 15 January 2026, a new and collective Vision for Breastfeeding and Infant Feeding in the UK was published through a process coordinated by Bremner and Co and commissioned by Impact on Urban Health through their Breastfeeding in Focus project. It was made possible through contributions and endorsement from the sector, including from us at First Steps. It was developed through a 3-phase process of engagement with breastfeeding organisations, practitioners, non-governmental organisations and academics across the UK, working together to articulate what all families should be able to expect from a supportive, equitable infant feeding system. The vision provides a shared foundation from which organisations can continue to collaborate, advocate and engage with policymakers with clarity and confidence.

The shared vision for the UK describes how the sector would like to:

Create supportive environments where breastfeeding is normalised and protected

Ensure all families have equitable access to trusted, independent infant feeding support, free from discrimination, misinformation and commercial influence

Deliver responsive, skilled support grounded in robust, evidence-based guidance

Strengthen dependable and resilient infant feeding support systems that reach every community

Secure a strong national commitment to high-quality breastfeeding and infant feeding support, through effective collaboration between government and organisations with recognised expertise.

You can read more about how the vision was developed in a Bremner & Co blog here and on the Impact on Urban Health website here.

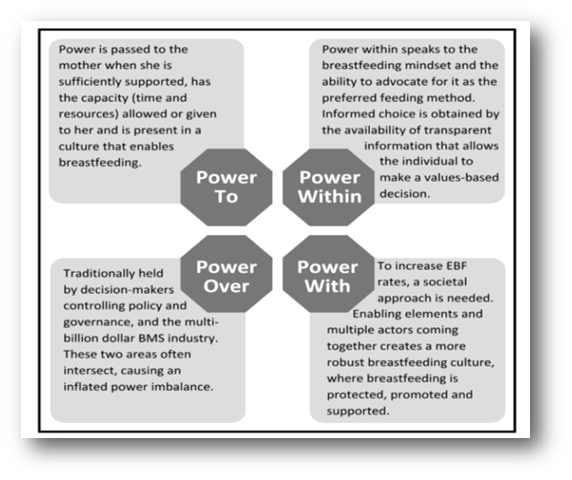

New paper: An exploratory analysis of enablers of exclusive breastfeeding in England: Positive deviance in practice

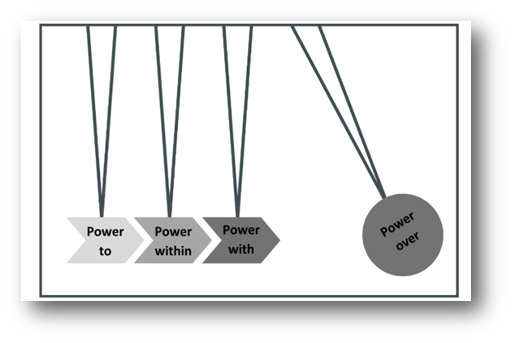

This new paper explored enablers of exclusive breastfeeding in England and was published in the December 2025 issue of World Nutrition. Twelve mothers, six midwives and two advocates from London, the East and Southeast of England were interviewed. The core themes identified were the position of breastfeeding in society; the role of agency in breastfeeding outcomes and navigating a way forward. The significance of power emerged as a dominant overarching theme throughout the findings, and so the researchers mapped the findings according to Gaventa’s power analysis, to contextualise the findings through a power lens (see Figure 3 below). The researchers describe:

“Each theme demonstrates the importance of a different expression of power and how, utilised effectively and collaboratively, they could be instrumental in disrupting the current mechanisms of power over preventing England from reaching breastfeeding targets, including ineffectual governance and the breastmilk substitute industry. The power framework has therefore been adapted as a continuum, with increasing impact on power over, and at its strongest together.”

(See Figure 4 below).

Figure 3: The findings of this research mapped to Gaventa’s power framework

Figure 4: A power continuum, based on the stylised idea of gaining momentum to displace an object. Power framework adapted from Gaventa

Useful appendices to the article include a timeline of measures to support infant feeding practices in the UK (from 1981-2022) and a PESTLE (Political, Economic, Social, Technological, Legal and Environmental) analysis of factors affecting infant feeding practices in England. Recommendations are provided at the end of the article, by examining positive deviance, and aim to contribute to future policy and strategic planning in England to support reaching global and national EBF targets. You can read more in the full article here.

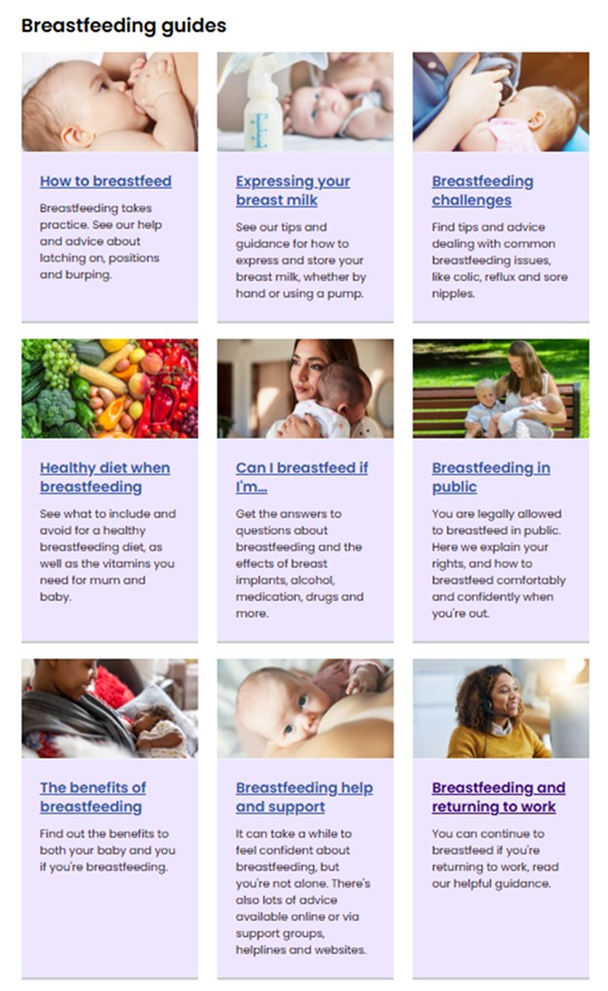

New: Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) Partnerships Team spotlight on breastfeeding resources

The Partnerships Team from the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) send out a monthly Early Years newsletter. During December 2025, this newsletter showcased the DHSC Breastfeeding resources that are available.

The Best Start in Life website was officially launched in September 2025 (to replace the previous Childcare Choices website).The December 2025 Early Years newsletter indicated that existing resources are in the process of being updated, and in the New Year will be rebranded to align with the Best Start in Life.

The Breastfeeding resources that are available include:

Various breastfeeding guides, wallet cards, posters, social media creatives for both breastfeeding and pregnancy, and the 'easy read' leaflet created in collaboration with UNICEF. These can be downloaded and ordered here.

A comprehensive selection of knowledge and guidance for breastfeeding families, providing NHS-trusted advice on topics such as expressing breastmilk, breastfeeding in public, maintaining a breastfeeding-friendly diet, the many benefits of breastfeeding, returning to work while breastfeeding, and many more. These can be found here.

The easy-read 'A guide to help you start breastfeeding' leaflet, created in collaboration with UNICEF, provides mums and parents with key information about breastfeeding. This resource is designed to support audiences with low literacy levels or where English is not a first language. This can be downloaded here.

To sign up to receive the monthly newsletters, go to the Campaign Resource Centre. You will need to register an account, and this will enable you to: download and order resources (including posters, leaflets and digital assets); access campaign toolkits, brand guidelines and logos; and receive email updates on new campaigns and resources.

News: Baby food hit by problems for pouches

On 12 December 2025, the Grocer published Babyfood hit by problems for pouches, reporting that the “wet babyfood category” declined by about 15%, following the April 2025 BBC Panorama investigation, with criticised brands being worst affected.

The Truth about Baby Food Pouches documentary aired by the BBC, which our Director, Dr Vicky Sibson featured in, concluded that several baby food brands have made misleading health claims about their pouch products. The documentary provided an opportunity to shine a light on long-standing issues with commercial baby and toddler food marketing in the UK, using much of the ongoing technical and advocacy work of several organisations, including us at First Steps. The documentary also provided new momentum to leverage long overdue improvements in the commercial baby food retail offer.

This decline in the wet babyfood category is likely due to the exposé and media coverage, as well as the concurrent adjustments made to the NHS guidance to parents that they do not need to rely on shop-bought baby foods, which was a request we made to the DHSC’s chief nutritionist. In August 2025, the DHSC also published the Voluntary industry guidelines for Commercial baby food and drink , effectively putting the baby food industry on notice to improve product composition and marketing. Businesses have 18 months from publication of these guidelines in August 2025 (i.e., they have until the end of February 2027) to implement both the salt and sugar targets and the recommendations on labelling and marketing. We hope that during 2026, through collaborative work, we can achieve positive progress in the baby food space in the UK, to contribute to creating an enabling environment for all babies to have the best start in life.

New paper: Understanding parents’ experiences of using a portion guide for young children: A qualitative study

New qualitative research has explored parents’ experiences of using an age-appropriate portion size guide for children aged 1–4 years (specifically the HENRY ‘how big is a portion’ guide), providing timely insights for policy and practice. The research was published online in December 2025 and conducted by Mira Malmber and Rana Conway at University College London and Beckie Lang at HENRY.

The study is relevant to the Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (SACN)’s 2023 report, Feeding young children aged 1 to 5 years, which highlighted that larger portions may contribute to higher energy intakes in young children, alongside National Child Measurement Programme data showing rising rates of overweight and obesity among reception-aged children. Despite the availability of several portion guidance tools in the UK, none are routinely provided to parents, and evidence on how families use them has been limited. SACN also highlighted the need to develop and communicate age-appropriate portion sizes for young children.

Interviews with 15 parents in England found that although guidance was welcomed, it had limited impact on portioning practices. Parents often found the guidance impractical or unrealistic, relying instead on their own experience and their child’s appetite and preferences. However, the guide was valued as an educational resource to support balanced diets and limit less healthy foods.

The research found that parents preferred picture-based, easy-to-access guidance delivered early in the complementary feeding period and from trusted sources, and noted that the FSNT eating well guides, are an example of good practice.

The authors conclude that portion guides alone are unlikely to change feeding behaviours and recommend more practical, holistic tools alongside greater investment in trusted early years services. We share this view and continue to advocate for parents and carers to have access to independent, evidence-based guidance through adequately resourced health visiting services and Best Start in Life Family Hubs, as set out in our joint position paper ‘Healthy Early Years Diets: Achieving the Best Start in Life’.

New policy paper: The Government’s Child Poverty Strategy

On 5 December 2025, the Government published its Child Poverty Strategy, called Our Children, Our Future: Tackling Child Poverty which was developed by the Child Poverty Taskforce. The strategy is considered a landmark commitment and key priority of the current government, aiming to lift 550,000 children out of poverty by 2030. The strategy acknowledges that the UK has higher child poverty rates than most European Union and Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, with nearly one-third of children in the UK being ‘in relative low income’. The strategy describes how the government, working with partners, will work towards tackling the root causes and alleviating the symptoms of child poverty, to give children the best start in life across the UK.

The strategy consists of 6 chapters:

The scale of the challenge and the case for change

Reducing child poverty in partnership

Boosting family income

Driving down the costs of essentials

Strengthening local support for families

Hope for the future.

It is significant that the role of food and nutrition, including in the early years, in contributing to optimal health and development, is acknowledged in the strategy. Infant feeding is described in Chapter 4 (Driving down the cost of essentials), including the investments committed to supporting infant feeding services and breastfeeding support through the Family Hubs and Start for Life programme, as well as the National Breastfeeding helpline. The cost of infant formula is acknowledged in the strategy, and the government’s response to the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) infant formula market study (see more on this below, in the section on BFLG-UK news) together with increasing value of Healthy Start vouchers are described as strategies to make it easier to access healthy, affordable food.

Other key components of the strategy (some of which had been announced previously but are now all consolidated in the strategy) include ending the two-child limit, expanding Free School Meals and implementation of School Food Standards and acknowledgement of the need to support children and families with No Recourse to Public Funds. The government had indicated that they will develop a monitoring and evaluation framework including annual reporting on the strategy.

For some helpful insights on the strategy, take a listen to a 10-minute podcast by Hannah Brinsden on the Food Foundation Pod Bites: Child poverty – are we failing?

For more information on supporting families, see our relevant resources:

New inquiry report: First 1000 days, a renewed focus

On 22 January 2026, the cross-party Health and Social Care Committee published the Fifth Report of Session 2024–26 on the Inquiry on the First 1000 Days: a renewed focus. The First 1000 Days Inquiry report acknowledges the first 1000 days as a critical window of opportunity for child development and recognises that the UK has some of the worst health outcomes for young children in Europe, including rising obesity, uneven vaccination coverage and persistent inequalities. The First 1000 Days Inquiry aimed to understand why there continue to be challenges in achieving progress for early years interventions and care in the UK, despite effort and ongoing commitments from multiple governments. The report was developed following submissions of written evidence (including our consultation response in April 2025), presentations of oral evidence and committee meetings. The current report focuses on the Family Hubs and the Start for Life programme, health visiting, the workforce, vaccinations and service integration.

We are pleased to see recommendations on making Family Hubs universal and improving investment into health visiting. However, there are insufficient measures described to ensure comprehensive support for early years nutrition. It is concerning that infant and young child feeding and early years nutrition are not being comprehensively integrated into national reports and recommendations. There needs to be much better policy alignment and coherence if the government is to achieve its commitments to the best start in life and raising the healthiest generation ever.

The joint position from us at First Steps, the Obesity Health Alliance and others, on ‘Healthy Early Years Diets: Achieving the Best Start in Life’, updated in December 2025 and supported by over 100 organisations, describes our shared policy asks on health early years diets. The joint updated position statement presents a clear, achievable set of evidence-informed and cost-effective steps that will measurably improve the nutritional quality of diets in the early years. The joint position recommendations call for bolder government action, including stronger legislation to protect families from misleading commercial milk formula marketing, and introducing a mandatory regulatory framework governing the nutritional composition, marketing, and labelling of baby and toddler foods, among other actions.

Infant Milk News

News: Recent price rises in formula milk products

We have identified increases in the price of some formula milk products since the publication of our cost report in October 2025. We are currently investigating these changes and plan to publish an updated, comprehensive cost report as soon as possible, during February 2026.

Parents affected by these price rises can be reassured that it is safe to switch between first infant formula brands. By law, all infant formulas must meet the same nutritional composition standards, regardless of brand or price.

These cost increases are particularly concerning as they run counter to the CMA formula market study recommendations to reduce formula prices. Any increase in formula price will place additional pressure on families with infants and potentially increase the risk of unsafe formula feeding practices. This also confirms our concerns with the Government’s response to the CMA recommendations (see below), where we feel that stronger action is needed in the short term to deliver meaningful impact for families and babies. It is critical that the Government proceeds with timely implementation of the CMA recommendations it has accepted, and describes how and when they will determine whether more direct measures are needed to improve infant formula affordability (such as the backstop option that was recommended by the CMA, namely prices controls, which could be achieved through profit margin caps).

Product updates: Infatrini and Neocate LCP

Nutricia has updated the composition of Infatrini, a Food for Special Medical Purposes (FSMP) for the dietary management of disease-related malnutrition and growth failure in infants and young children. The revised formulation now includes 2’-Fucosyllactose (2’-FL) and added prebiotics (short-chain galacto-oligosaccharides and long-chain fructo-oligosaccharides). There is no good evidence that these additions provide benefits for infants when added to infant milks, and they are therefore considered unnecessary. The energy, macronutrient and micronutrient composition remains unchanged.

Neocate LCP, an amino acid-based FSMP suitable from birth for non-metabolic disorders, has been updated to a 420g tin with new packaging (previously 400g). The formulation is unchanged except for a switch in the source of Docosahexaenoic Acid, from Crypthecodinium cohnii oil to Schizochytrium sp. oil; both are microalgae-derived.

As a reminder, specialist infant milks marketed as FSMPs should only be used under medical supervision, as stated on product labels.

More information on milks marketed as FSMPs can be found in our reports: Specialised milk for infants who are premature, low birthweight or have faltering growth and Specialised milks for infants with allergies.

News: Nestlé and Danone Infant Formula and Follow-On Formula product recall

It has been confirmed that some batches of various Nestlé formula milks sold in the UK under the SMA and SMA Little Steps brands, as well as a Danone product sold under the Aptamil brand, have been contaminated with a toxin called cereulide. This toxin can cause food poisoning. The symptoms are nausea, vomiting and cramps very shortly after consumption.

Further details, including the affected batch numbers, are available in the food alerts issued by the Food Standards Agency since Friday 5 January 2026.

The alerts are as follows:

24th of January Danone recalls Aptamil First Infant Formula because cereulide (toxin) has been found in this batch | Food Standards Agency

3rd of February: Update 2: Nestlé recalls several SMA Infant Formula and Follow-On Formula because of the presence of cereulide (toxin) | Food Standards Agency

The recalls extend beyond the UK, affecting more than 60 countries, and have attracted national and international media attention. On 6 January, our Director, Vicky, spoke on BBC Radio at lunchtime, and our Senior Nutritionist, Katie, appeared on the ITV evening news. FSNT also contributed to an article in the Financial Times: Nestlé and Danone hit by backlash over contaminated baby formula.

The contamination has been traced to arachidonic acid (ARA) oil. Current UK legislation regulating infant formula (Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2016/127) mandates the addition of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) to infant formula. The Codex Standard for Infant Formula, however, considers DHA to be an optional ingredient, but that if DHA is added to infant formula, then the same amount of ARA should also be added. This case highlights how microbial contamination of a single source ingredient can have global repercussions, particularly in the commercial infant formula industry, which operates within a profit-driven supply chain that pressures companies to source low-cost ingredients.

Advice for parents and carers using the affected formula milk products

It is vital that parents using any of the affected formula milk products check the batch numbers and stop using any that are listed as potentially contaminated (batch numbers that are not listed can continue to be used). If the baby is sick, the parent should contact their GP or call 111.

All parents and carers should be aware that it is perfectly possible and safe to switch brands of first infant formula as they are all nutritionally equivalent. There may be a period of adjustment as baby gets used to the new formula. Some babies may take a short time to adjust, and parents and carers may notice some temporary changes in their stools, as different ingredients are used in different brands. If a parent has any concerns they could contact their health visitor for advice, or their GP or 111.

Not all milk is suitable for feeding babies. Babies under one year of age should never be given condensed milk, evaporated milk, dried milk, goats’, sheeps’, cows’ milk or plants based milk drinks such as soya, rice or oat (as a drink) as outlined in NHS guidance on milk feeding babies under 1.

Home-made infant formula is not safe to use as it does not have an appropriate nutritional composition and therefore may not support proper growth and development, and the ingredients themselves, or the way in which they have been prepared, increases the risk of severe bacterial infection in infants.

The NHS recommends that non breastfed or mixed fed babies can be given infant formula up to 12 months of age and that follow-on formula is not necessary (and should never be given to babies under 6 months old).

Babies being fed one of the affected non-standard formulas (anti-reflux, comfort, lactose-free, or Alfamino) should consult their health professional for advice on a suitable alternative.

First Steps Nutrition Trust provides independent expert information about all formula milks on the UK market for parents and carers here: https://www.firststepsnutrition.org/parents-carers

Advice for health professionals

Health professionals can use our website www.infantmilkinfo.org to look up alternatives to the affected products to advise parents; see the tab ‘type of infant milk’ and look up lactose-free under infant formula, as well as comfort and anti-reflux. Information on alternatives to Alfamino are in the report “specialised milks for infants with allergies”.

Supporting all parents and carers who use infant formula

The recall comes shortly after the ByHeart powdered infant formula recall in the USA, which we reported on in our December newsletter. Together, these incidents reinforce the importance of reminding those using formula to feed their babies, that powdered infant formula is not sterile and that NHS guidance must be followed carefully when preparing feeds.

A key element of this guidance is ensuring that the water used to reconstitute the powder has been boiled and allowed to cool to no less than 70°C to kill any bacteria present in the powdered infant formula.

We also advise against using formula preparation devices, or at least checking the temperature of the hot shot as per NHS advice, as our research has shown they do not consistently heat water to 70°C and therefore may not effectively eliminate bacteria in powdered infant formula.

More information on safe formula preparation can be found here.

Infographics on safe formula preparation, suitable for sharing directly with families, are available here.

Policy recommendations

Intrinsic contamination of powdered infant formula has been documented repeatedly over decades, leading to numerous recalls and harm to infants. These incidents expose systemic failures in formula manufacturing, regulatory surveillance and communication of risk to parents and carers, reinforcing the need for stronger regulations to protect infant health.

On 2 February 2026, the European Food Safety Authority announced plans to update its scientific advice on cereulide, including setting a toxin threshold to trigger recalls. While welcome, this highlights the reactive nature of current safety systems.

Furthermore, the advertising and promotion of commercial milk formula suggest to parents that these products are inherently safe. This reinforces the urgent need for full implementation of the international Code and relevant World Health Assembly resolutions, which require clear warnings about the non-sterile nature of powdered formula milks.

We at First Steps are advocating for stronger independent oversight of formula manufacturers, improved monitoring of illness linked to formula feeding, and mandatory labelling to clearly state that powdered infant formula is not sterile and must be prepared according to NHS guidance. We also want to see the rules governing the addition of non-mandatory ingredients to formula milks to be revisited.

At the global level, the International Baby Food Action Network (IBFAN) is in Geneva this week urging Member States to adopt a new World Health Assembly resolution to reduce contamination risks for infants. Given the global nature of formula production and supply chains, such action would directly support and strengthen UK advocacy efforts.

Our Statement on Nestlé and Danone formula milk recalls, the first document on our First Steps Statements webpage provides latest information for parents and health workers, and we aim to keep this as up-to-date as possible, as new information becomes available.

New paper: Infant formula milk shows microbiological contaminants that are not removed using recommended preparation methods

New research from Queen’s University Belfast (published in October 2025) highlights concerns about the microbiological safety of powdered infant formula (PIF), particularly when prepared using at-home preparation machines (AHPMs). The study examined 21 UK PIF products prepared using NHS-recommended 70 °C water, boiled and cooled water, and AHPMs. All products were suitable from birth to six months and marketed for use with AHPMs.

Microbial contamination was detected in around one-third of products tested, with Bacillus species most commonly recovered, including Bacillus cereus, a known infant pathogen that produces cereulide toxin, associated with infant illness and the current recall of Nestlé and Danone infant formula milks products sold in the UK . Although contamination was observed across all preparation methods, significantly higher microbial levels were found in formula prepared using AHPMs, even when sterile water was used.

These findings align with our research conducted with colleagues at Swansea University, which shows that formula preparation devices frequently fail to deliver water at temperatures sufficient to reduce bacterial risk (>70 °C). The study also showed that rapid cooling of prepared formula may reduce the effectiveness of heat treatment, allowing surviving microbes to persist.

Together, these findings raise concerns about the safety of widely used formula preparation devices and highlight the need for further investigation by the Office for Product Safety and Standards, alongside clearer NHS guidance on their use in the interim.

We therefore continue to recommend avoiding formula preparation devices (like the Tommee Tippee Perfect prep) machine or at least checking the temperature of the hot shot as per NHS advice.

We now also suggest avoiding rapid cooling devices like the Nuby Rapid Cool, until further research shows that rapid cooling does not disrupt the effect of the hot water used for making up the formula, to kill any bacteria that may be present.

For resources to support families who use formula to feed their babies, see our Infant milks: Information for parents and carers webpage and our Formula choice and preparation infographic.

If you have any questions about accessing the site, please email us at admin@firststepsnutrition.org.

For infant milk information please visit our website www.infantmilkinfo.org. If you can’t find what you’re looking for please email rachel@firststepsnutrition.org

Baby Feeding Law Group news

New video: What are the solutions to the infant formula affordability crisis?

On 27 January 2026, Prof Amy Brown at Swansea University and colleagues shared a 3-minute summary video on YouTube summarising key messages from research looking at the impacts of and solutions to the infant formula milk affordability crisis. The research included interviews with 281 parents who were struggling to afford formula, and 158 professionals and volunteers who support parents. The research was led by Swansea University, together with partners at Cardiff Metropolitan University, The University of Hertfordshire, the Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Trust, the Independent Food Aid Network, Leicester Mammas, and us at First Steps Nutrition Trust.

Findings from the research included that the cost of infant formula was having a devastating impact upon families, and parents reported feeling distressed, anxious, and heartbroken that it was so challenging to feed their infants. Poor affordability was found to exacerbate postnatal depression. Parents reported going into debt, skipping meals and not heating their homes to pay for infant formula. Some also reported unsafe practices such as watering down feeds and looking to Facebook marketplace to purchase infant formula, knowing that this could put their baby at risk, but not seeing an alternative. Many parents spoke of being angry at the high costs, much of which goes to marketing and profits of the infant formula companies. Solutions such as an emergency pathway led by councils or the NHS were suggested, however many parents just wanted formula to be cheaper. Any solution that didn’t reduce the cost allows companies to continue making high profits and passes the problem to the taxpayer.

The researchers made the following key recommendations to the Government:

Prioritise acting on the Competitions and Markets Authority’s 11 recommendations from their infant and follow-on formula market study

Regulate the price of infant formula

Ensure better support for breastfeeding

As secretariat for the Baby Feeding Law Group, we fully support these recommendations. Marketing and pricing are intertwined. Formula marketing needs to be reined in through strengthening UK laws in line with the Code and resolutions and enforcing them properly. Infant formula prices need to be reduced sustainably and in the long term through Government regulation. These actions will contribute to giving all babies the best start in life. The full research paper is currently under review and will be published shortly.

New policy paper: Joint Government response to CMA formula market study

On 3 December 2025, the Government published its joint response to the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) infant and follow-on formula market study. The joint response was compiled by the UK, Scottish and Welsh governments (including the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), Public Health Scotland, Public Health Wales), Food Standards Scotland, and the Department of Health and Food Standards Agency in Northern Ireland.

It is significant that the government have formally acknowledged the longstanding issues with the formula market in the UK, relating to marketing, pricing and retail practices which undermine public health infant feeding recommendations. The government made several notable, positive commitments for which they should be praised. However, the current response relies on a non-legislative package of measures, and it our view that further actions will be needed in the short term to deliver meaningful impact for families and babies, especially those on low incomes.

The Government accepted (“in principle”) six of the CMA’s 11 recommendations, committed to “further work” on three and rejected two recommendations. The CMA had indicated that governments may wish to consider price controls for infant formula as a backstop option, if the CMA’s proposed package of measures does not achieve the desired market outcomes and if the impact on consumer outcomes is insufficient within a reasonable timeframe. Unfortunately, the government response does not mention this potential future option. We feel it is critical that an adequate timeframe is determined for when this be reviewed, and detail should be provided on how impacts will be monitored. If infant formula prices remain high in mid-2026 (and we have identified increases in the prices of some formula milk products, as described above in Infant milk news ), a formal assessment should be conducted on the need for and feasibility of implementing more direct measures to improve formula affordability (such as price controls through profit caps).

It is important that, for the six recommendations accepted in principle, these should be implemented in a timely manner, with further detail provided on the indicators to be used for monitoring impact and whether further steps are required. For the three recommendations requiring further work, there should be clarification on the next steps to strengthen labelling and advertising rules, and clear timelines for how this will be conducted. The goal should be stronger regulations in line with ‘the Code’, placing restrictions on advertising of all formula milks marketed for use up to 3 years, and proper enforcement. This would put children’s wellbeing above commercial interests. We will shortly be sharing a comprehensive BFLG-UK statement on the Government response to the CMA report, which will be available on the BFLG-UK website here.

A reminder: What YOU can do to challenge conflicts of interest (such as the upcoming formula-sponsored British Journal of Midwifery conference)

We have compiled a comprehensive list of suggestions for what healthcare professionals can do if they identify conflicts of interest, especially relating to challenging the inappropriate marketing of breastmilk substitutes or commercial milk formula targeting health professionals. See the suggestions provided on our First Steps Nutrition Trust website here.

The annual British Journal of Midwifery (BJM) conference is taking place on Tuesday 31 March 2026, with sponsors including Kendamil and Nutricia (Danone). We have previously written public letters to the conference organisers, have had commentaries published in the British Medical Journal, and we have directly emailed the conference organisers, but these have not resulted in any changes to the conference sponsorship policy. We encourage other individuals and organisations to send letters to the organisers and/or make public statements to create greater awareness of this problematic conflict of interest. The conference is organised by the Mark Allen publishing group and the names of contact people and their email addresses are available on the conference website here. Perhaps with continued pressure and advocacy, the organisers will change their policies in future, and/or fewer health professionals will attend and/or fewer speakers will agree to present at such conferences.

For more information about the BFLG-UK please visit our website Baby Feeding Law Group UK (bflg-uk.org) and sign up to our twitter (X) account @BflgUk. You can also email katie@firststepsnutrition.org

Forthcoming

Conference: iHV Evidence Based Practice conference Bournemouth May 6th

The Institute of Health Visiting (iHV) will be hosting a full-day Evidence-based Practice Conference 2026, with the theme “From Evidence to Action: Getting it right from the start”, at Bournemouth International Centre on Wednesday 6 May 2026. Our Director, Dr Vicky Sibson will be doing an oral presentation on Starting solids and the latest public health recommendations on shop bought baby foods. You can book your tickets here before 7 March 2026.

Updated resource: Eating Well Healthy Start and Best Start Foods: A practical guide

Our Eating Well resource Healthy Start and Best Start Foods – A practical guide was last updated in 2022. In light of the recent announcements to increase the value of the Healthy Start vouchers in April 2026, we will be updating this resource to reflect the increase in allowance. We will also be looking to develop posters, leaflet and recipe cards for use in Family Hubs and food bank settings and will share when these become available.